Paul McGaha and his colleagues in East Texas are raising awareness of, and providing screening for, colorectal cancer.

By Daniel Oppenheimer

Editor, Texas Health Journal

Dr. Paul McGaha doesn’t sugarcoat the challenges of promoting colorectal cancer screening. It’s not everyone’s favorite medical test, and it can be hard to get people either to take the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) at home or to visit the doctor for a colonoscopy. McGaha is quite bullish, however, on screening and education programs like the one that he and his colleagues run out of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler.

The reason is simple. It saves lives.

“If precancerous polyps are detected early, colorectal cancer is very preventable,” said McGaha, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Community Health at UT Health Science Center at Tyler. “In some cases a skilled physician can remove the polyps during the screen itself.”

Paul McGaha, DO, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Community Health, UT Health Science Center at Tyler

Since the colorectal cancer screening program was launched four years ago, with a grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), it has screened thousands of uninsured people in East Texas, which is the region in Texas with the highest death rates from colorectal cancer. It has also educated more than 1,500 health professionals across 19 counties in the region and provided education and outreach to thousands more.

Over the course of its work, 56 of the people screened have exhibited precursors to colorectal cancer, and 14 more have been diagnosed with cancer. All of them have been referred for further treatment.

“As a general rule, people should be screened between the ages of 50-75,” said McGaha, who was a Regional Medical Director for the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) Health Service Region 4 and 5 (North) for 19 years before joining the faculty in Tyler. “The vast majority of new cases, about 90 percent, occur in people who are 50 or over.”

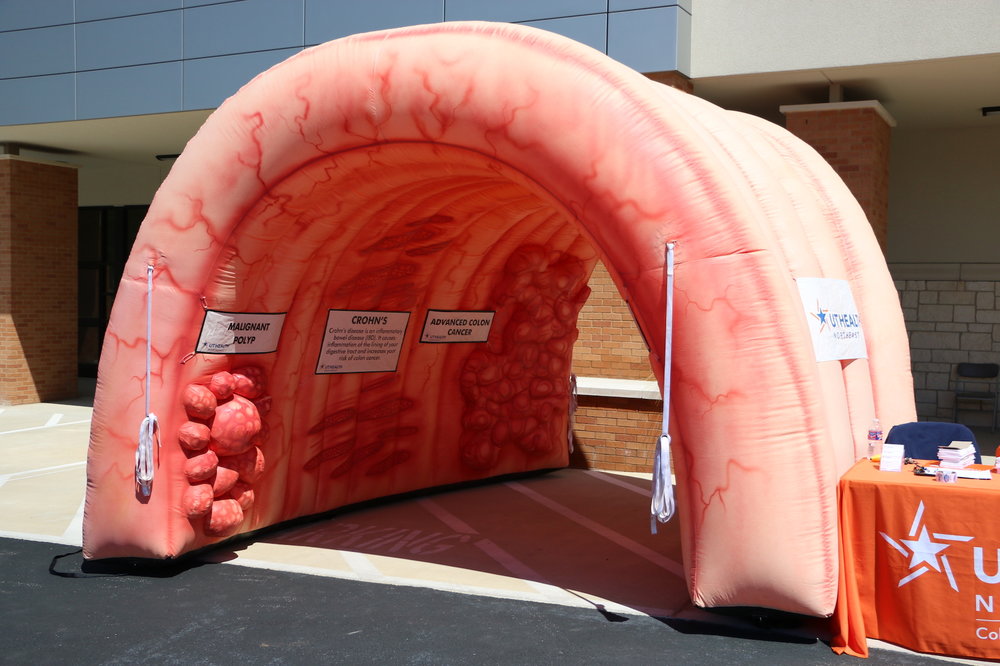

In order to help spread the word about the need for screening, McGaha and his colleagues travel around the region with a massive inflatable colon. People can walk through the colon and see both precancerous and cancerous lesions

“It’s about size of an office,” said McGaha. “It gives people a great sense of what the doctor is looking for.”

The traveling inflatable colon allows people to better visualize what physicians are looking during screenings.

The inflatable colon, and other educational materials and activities, are intended both to funnel people directly into the screening program and to raise awareness, more broadly, about the need to get screened.

“Our screenings are provided free of cost for people who don’t have insurance, but that is not the only group that isn’t getting screened adequately,” said McGaha.

Many insured people, said McGaha, aren’t regularly going to the doctor, so they won’t be told to get screened. Even many of the people who do get a recommendation from their provider to get screened won’t follow up.

McGaha understands the reluctance. Colonoscopies are invasive procedures. They are also time-consuming, once you add in the prep before and the recovery from anasthesia after. He’s convinced, however, that access to screening and high quality information really can change the equation.

“You talk to gastroenterologists, who are the ones who typically perform colonoscopies, and they just have saved so many lives,” he said. “So often they’re removing polyps that aren’t too bad, they’re small, but given 5 or 10 years would be the ones that would develop into stage 3 or 4 cancer. That’s extraordinary. It’s a cure. And getting screened, despite the inconvenience, is so much better than finding out too late that lesions that could have been removed have developed into cancer.”